When De Beers took control of the diamond market a century ago, the company defined the standard of beauty for diamonds as a clear, colourless stone. As a result, coloured diamonds were generally overlooked up until a few decades ago, while brown diamonds were considered unsuitable for jewellery altogether. Today, brown diamonds are finally showing their true colours, growing in popularity as unique and popular stones.

Brown diamonds have a brown body colour, with modifying hues of red, orange or yellow. The body colour is said to be derived from pressure on the diamond crystal lattice as it was formed in the Earth, changing the way that light absorbs and transmits through the diamond. For decades, the colours within a brown diamond were not considered marketable, so the stones were set aside for industrial purposes, such as being crushed to make abrasive granules.

However, faced with an increasing supply of brown diamonds – in the Argyle mine for example, 80% of diamonds were brown – the diamond industry needed to find a lucrative way to market this stone as jewellery. Around 80% of Argyle’s rough were brown diamonds under 0.1 carat in size, and most of the stones had clarity issues. Rather than sell the diamonds to De Beers for industrial use, Argyle sent the diamonds to India to be cut into tiny round brilliant diamonds, which were used to enhance jewellery pieces. Turning larger brown diamonds into jewellery proved a little more challenging – while brown diamonds had a unique beauty of their own, the market needed to be convinced.

The first challenge was to assign a value to the gemstone they had once discarded. As the value of brown diamonds could not be determined by the original grading system, Rio Tinto created a new grading system going from C1 representing the lightest colour to C7, the darkest.

The second challenge was to rename the brown diamond in a way that would catch the public imagination. When diamonds had been marketed for a century as being synonymous with light and sparkle, “brown diamond” seemed like a contradiction in terms. The campaign to rebrand the brown diamond was a slow process, but ultimately highly successful.

“If you start to use descriptives such as champagne or cognac rather than brown, the diamonds start to sound more appealing,” said Troy Reany, general manager of Lost River Diamonds. “I think Argyle did a great job of telling us that their diamonds were beautiful and unique and our part of an Australian story.”

“Faceting coloured diamonds is a different art to those that are near-colourless as the objectives are opposite,” said John. “For near colourless diamonds, you want to minimise any colour is preferable, whereas for coloured diamonds, your aim is to maximise the colour. As a result, the majority of coloured diamonds have fancy shapes rather than being round brilliants. The facets are angled to steer the light within a stone for as long a path as possible. This art has allowed many faceters to profit from recutting diamonds and achieving a higher colour grade.”

Located in Perth, Western Australia, Lost River Diamonds source the highest standard of coloured diamonds and white diamonds from all over the world. The company takes pride in the highest and most consistent grading standards possible.

Troy says that champagne diamonds are particularly popular with consumers right now.

“The key with champagne diamonds – and in fact any coloured diamond – is the uniqueness of the colours,” Troy said.

While Argyle successfully implemented the idea of branding brown diamonds with exotic names, it was US diamond cutter and fine jewellery importer, Baumgold Bros, who first introduced names like champagne, amber, cognac and chocolate in order to market brown diamonds as quality gemstones in the 1960s. Other jewellers followed their example, but in the beginning, this practice was more confusing than illuminating, as there was no industry consensus about the names for various hues.

The Baumgold Bros were also responsible for cutting the Earth Star (111.59 ct) a pear-shaped diamond with a strong brown colour and extraordinary brilliance, which was discovered in 1967 as a 248.9 carat rough. It was the largest polished brown diamond in the world at that time, and the third largest brown diamond in the world today.

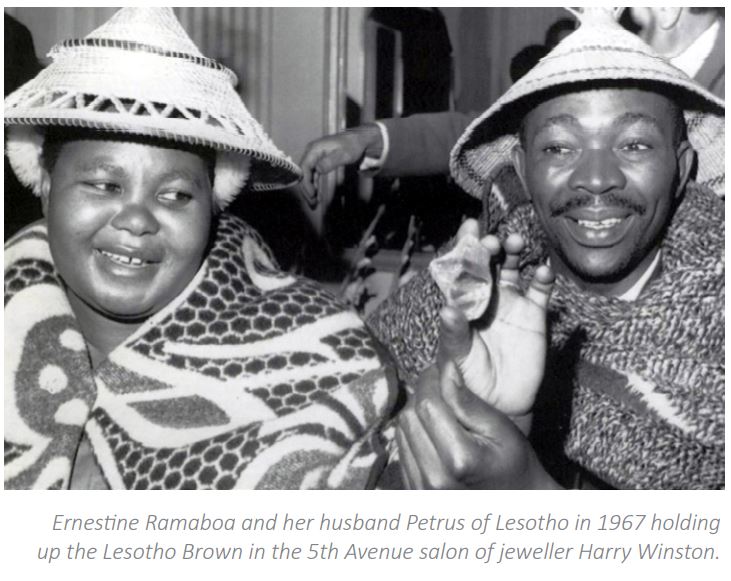

Also in 1967, a woman named Ernestine Ramaboa, the wife of a Lesotho miner, stumbled upon an enormous rough brown diamond, weighing 601 carats. The penniless couple reputedly walked for four days and four nights to deliver Ernestine’s discovery to a reputable diamond buyer in Maseru, the capital of Lesotho. The Lesotho Brown is still the largest diamond ever discovered by a woman and the seventh largest rough diamond ever discovered. Once cut and polished, the Lesotho Brown yielded 18 gemstones totalling 252.40 carats, and the third largest stone – the Lesotho III, a 40.42 carat marquise cut – was set into the engagement ring of Jackie Kennedy Onassis. In 1974, Elizabeth Taylor wore a cognac diamond ring and earrings to the Academy Awards, a gift from Richard Burton for their tenth anniversary.

While these discoveries and celebrity endorsements raised the profile of brown diamonds, the influx of coloured diamonds in the 1980s overshadowed brown diamonds for another decade, as even colourless diamonds were outshone for the first time in a century.

“Coloured diamonds soon appeared on the radar of consumers – pinks, browns and yellows and other colours, notably blue and to a lesser extent – greens,” said John Chapman, director of Gemetrix.“In the fancy intense and vivid ranges, all these colours except brown attracted higher prices than colourless stones and over time the gap has widened, spurred on by prominent auctions and celebrity exposures that bolstered publicity and messages of rarity.”

Gemetrix provides unique consultation services in the diamond industry, in relation to data analysis, diamond technology and process trouble-shooting.

Brown diamonds cut to maximise their colour will reveal rich and warm hues of pink, orange, yellow or red, creating a unique fire and individual colour. Now social media sites like Instagram are overcoming the stigma of the word “brown” as photographs of brown diamonds reveal the true beauty and versatility of all their hues.

“I think people are drawn to the one-off nature of the colour and knowing that you won’t find two the same,” said Troy. “That in itself is a trend as people want something a little bit different to the next person.”