Recently, at the Jewellery Industry Fair, Ashie Luke spoke to Damien Cody, the president of the International Colored Gemstone Association.

AL: You have a unique vantage point in the jewellery industry. How do you see the intersection between the global coloured gemstone market and the Australian jewellery industry and what insights can you share about that symbiotic relationship?

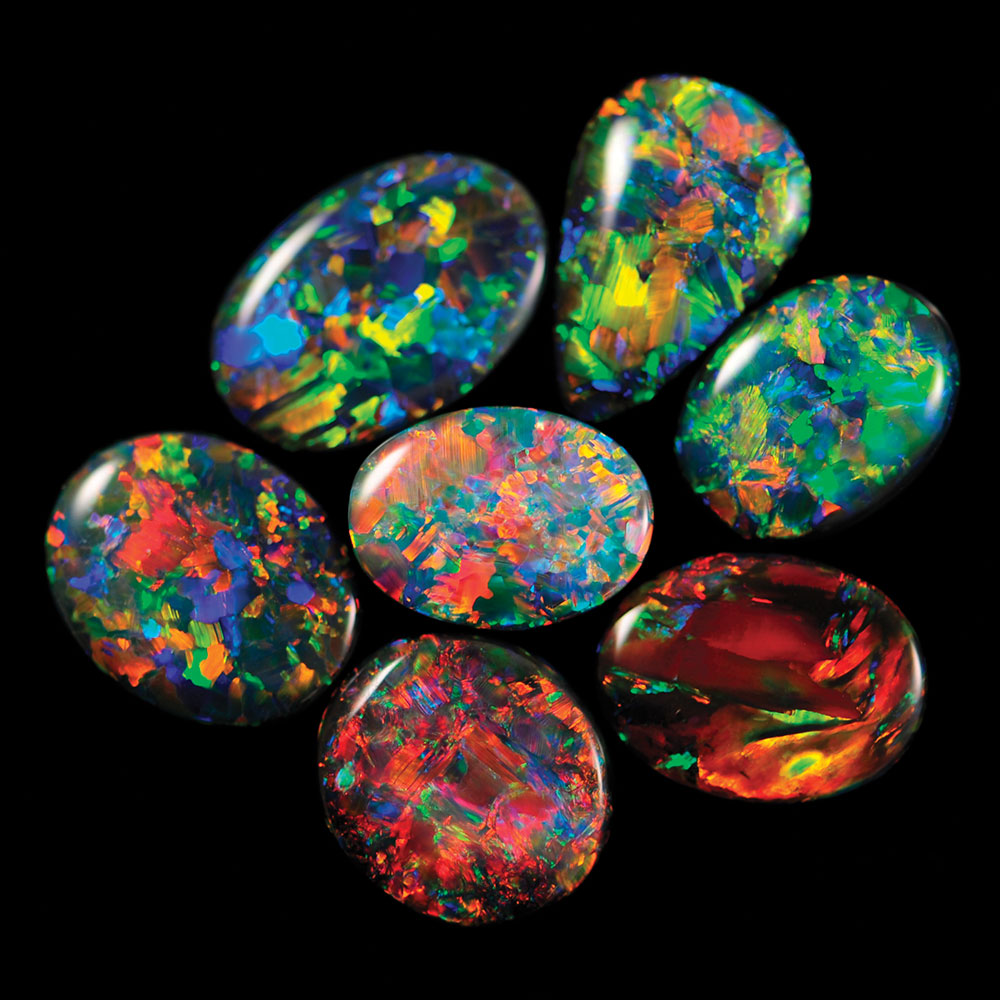

DC: Australia is a big producer of gemstones. Australians don’t necessarily appreciate their own gemstone, but obviously, we’re the biggest producer of opal in the world. Not necessarily in terms of quantity but in terms of value. We are a strong player in the sapphire market and they’re enjoying a resurgence at the moment.

DC: Australian sapphire used to be the realm of the Thai dealers who would come and buy the whole complete run of mine. What they would do is treat it and sort it, and the dark, ugly stuff was called Australian sapphire and the beautiful, bright colours were just put into the mix with Thai and Sri Lankan and whatever, so Australia got a bad wrap out of that. Now, we have producers mining Australian opal again because they’ve got a product now that is being marketed around the world and shown for its true beauty.

DC: That makes me so proud when I’m at a trade show somewhere in the world and here we have Australian sapphire which used to be really put down being promoted as a really special product—you know, the party colours and the unique nature about Australian sapphire. We’re also producing small amounts of ruby and other gemstones, but Australia has great credibility and kudos for being able to produce these goods in a first-world environment.

DC: Today, I spoke about consumerism and their demand for responsibly and sustainably sourced materials. It’s very difficult for some countries to be able to show their credentials, but Australia is perfectly placed because obviously, we have environmental laws, we have money laundering rules and regulations, we have occupational health and safety, checks and balances, we’re highly organised. So, even though we’re mostly small artisanal mining operations with gemstones, we have great credentials.

DC: In the case of Australian opal, for instance, we tick off nearly every box in terms of being a responsibly sourced product. We actually did a research paper I was involved with that demonstrated that Australian opal can more than likely be the most [ethical] gemstone mined in the world. It’s a great thing to hang our hat on.

DC: Australia is also an important consuming market, it’s growing. Our economy is very strong and the envy of many countries around the world and it’s endured some pretty tough times. Even at this trade show here we see quite a number of international suppliers coming in and in my role as president of the ICA, I’m constantly asked about the Australian market and the potential for them to bring their product and sell and I say “Come and give it a go.” The reality is that Australian jewellery consumers are conservative by nature, so they’re not wearing gregarious, very flashy things so much. They’ve obviously got a good appetite and a good, strong economy and whilst jewellery might not be high on their list, [it] probably falls a very poor fourth or fifth, it’s growing.

AL: What excites you the most about participating in this Fair and sharing your expertise with the attendees?

DC: I love the idea of the Australian industry being together, but we don’t get a chance—I guess I’m in so many international shows that I’m seeing so many international dealers on a regular basis—as an Australian forum we don’t get together very often so this is a great opportunity for Australian retailers to see some top-class, Australian suppliers and also a smattering of international suppliers. It’s a great opportunity.

DC: I had one guy yesterday say to me “I wish we had one of these every month in Australia,” but I said, “Come on, it’s so difficult to organise and for the exhibitors to get themselves here.” Yes, it would be nice but what Australian retailers and buyers who come to these events have to realise is that it’s a great opportunity. This is where you can have some incredibly good suppliers in one place, in a condensed period of time and it should be on their calendar every year to make sure they get here to do their buying.

DC: We live in a global environment. People think that they have to go to Hong Kong or to Las Vegas to get the deals. You don’t have to. They’re right under your nose, right here. Our product is priced the same, it’s actually cheaper than it is in overseas markets because of the currency situation, so we’re selling here in Australian dollars and overseas we’re selling in US dollars, which gives us a bit of an advantage.

AL: The jewellery industry is constantly evolving and influenced by consumer preferences, technological advancements, and market trends. From your perspective, what are some of the most noteworthy changes you’ve observed and how can professionals leverage these changes for their business?

DC: Social media has changed the landscape quite dramatically, so it doesn’t matter whether you’re selling online directly to consumers or whether you’re using the internet to promote your product or your brand. It certainly changed the way we do business.

DC: You have a great product in the magazine [JW Magazine], people still like that hard copy, so that probably hasn’t changed so much, but you are also going online with stories and articles and getting people to your product and your website. It’s a great conduit for the industry to talk to consumers and their customers at whatever level in the pipeline they are.

DC: Today I spoke about the real strong push by consumers for a transparent supply chain, for sustainably responsible products and I think in the coloured gemstone field we need to just be a little bit careful with all that. It’s simply not possible really to have a transparent supply chain in a coloured gemstone market. I’ll give you an example: most coloured gemstones are actually found in very remote areas of the world. They’re found, or mined, by very small operators, artisanal miners. I’ll give you an example: a person in a riverbed in Tanzania sifting through river gravels looking for secondary deposits of sapphire. Now that’s a very small operation. There is no internet, they’re in the mountains. They see a broker, or somebody sourcing the goods comes in on a motorbike once every month or so and buys their goods from them and takes them away to a larger city and to brokers and then it starts getting into the real supply chain. But there’s no way we can formalise all that, and nor should we. This is a mother and their children and their extended family sifting through riverbed gravel. It’s their livelihood. We can’t take that away from them simply because they haven’t logged into a computerised, formal environment so that we can track the supply chain.

DC: In the coloured gemstone world, there are really only very few supply channels that can confidently go from mine to market. They’re a very small proportion of the actual production, so why push for it? All you’d be doing is pushing all the business into the hands of the very big operators, the very big miners, and taking it away from the hundreds of millions of people involved in the supply chain, whether they be artisanal miners, or cutters, or treaters, or dealers. Even the dealers have a big role to play.

DC: If you imagine an Indian coloured gemstone dealer, six, seven, or eight generations in the business, they are going to the source to buy. They are cutting, treating, aggregating, sifting, grading, and they’re distributing around the world. There’s a lot of work involved with all of that so that a jeweller in New York can say “I want ten, matching, 8mm round pink sapphires,” for instance. They don’t just grow on trees. They started in a riverbed. So we should embrace all of that and celebrate all these incredible people along the supply chain who, in my role as president of ICA, we understand very well. But consumers may not understand that. But it’s a beautiful story, so rather than enforce something that’s impossible, we should embrace it and help it.

AL: You said in your talk today that the consumer isn’t more ethical, they’re just more aware. Would you like to elaborate on that?

DC: I think consumers [want] something that is branded as ethical, responsible, or sustainable, but they don’t really understand it. They’re more aware, but they’re certainly not more ethical because they’re not practising it themselves. They’re buying their disposable mobile phone which is made obsolete after a couple of years or a computer, a television or a car, and the componentry and the production and the incredible amount of detriment those things cause on our environment, whether it be from mining the raw materials or the production and the manufacture of all the components, or whether it be the e-waste at the end, is astronomical. But nobody really worries about it. Most people don’t worry about it.

DC: We all continue to buy a new mobile phone every two or three years and we’re forced to in many cases as well. So why target an industry that is actually quite beautiful and has very little impact on the environment? The mining and the distribution of coloured gemstones [have] a very low footprint, so let’s enjoy it. Let’s learn more about it. Let’s hear the stories. The multi-generational families that have been working in this industry for hundreds of years and the number of people they support, the number of families in these third-world countries who are supported by this industry. So let’s enjoy it. These beautiful gemstones are in many cases hundreds of millions of years old.

DC: Australians should understand more about the Australian opal for instance. 98 percent of it is exported overseas. Why is that? Why aren’t Australians enjoying something so beautiful and so rare and so unique that’s right under their nose and yet there’s little demand for it locally? So, let’s understand it a bit more, embrace it and enjoy it.

AL: Having shared your insights on the coloured gemstone market and its influence on the Australian jewellery industry, could you elaborate on some specific market trends that you’ve highlighted during your presentation that are poised to have a transformative impact on the future of the coloured gemstone trade in Australia?

DC: I touched on a few things. There are some conflicts around the world that have meant that we have these bans being imposed, so that is going to impact more and more. It hasn’t happened so much here in Australia, but governments are starting to get on top of things and understand what’s happening and how they can stem the flow of money back to some of these strife-torn or conflict zones. That’s a reality that we have to live with. At ICA we’ve been asked about the situation in Myanmar, Burma. We have the Burmese ruby which is being used by warlords to build their wealth. So there are bans around quite a few countries, with America being the biggest one. We understand the reasons why and we support that, but we also need to understand the impacts. The impact is that tens of millions of people in these areas now have no livelihood. They’re the forgotten ones. So, to stop a few warlords, we’ve now turned the lives of tens of millions of people completely upside down and they have no income and very little industry to go to. So they’re the forgotten people.

DC: At ICA we’re trying to make people more aware of that because too many people sitting behind a desk in a tower somewhere are making decisions and we need to understand all the ramifications. So they’re things we are trying to get a handle on so that we can go to the NGOs and the UN and to OECD and give them the background on how these decisions are impacting people. It’s not to say that we shouldn’t be making these decisions, but maybe we need to support these people who are the forgotten ones.

AL: As an influential figure in the industry, how do these affiliations contribute to your ability to foster change and share valuable insights at events like today?

DC: People [ask], “How did you become president?” and my answer to that is, I didn’t start out this career to become president of an international body. For any of the committees and charities that I work on, it’s just a sense of duty really. I’ve been involved in things and I’m always happy to contribute and I try and do things to the best I can. As a result of that somehow you keep getting pushed forward and into these roles. This latest position as president of ICA, it’s a huge honour. It’s a huge job but I wouldn’t say it’s overwhelming because I’ve got a good team of people to help. But I sit back sometimes and think I’m just a little Aussie battler in Melbourne, applying my trade and now all of a sudden I’m representing a huge industry. Not just our members, but hundreds of millions of people that we represent.

DC: It’s not something I take lightly, I’m probably not sleeping as much as I used to because I am constantly thinking and I’m involved in so many committees. And because we live in Australia, we’re very lucky, but the timezone thing is a killer. I’m doing Zoom meetings at one or two am, probably on average two or three nights a week. I have to keep time for the things I like to do in life as well, as for family and friends, so it’s a balancing act.

Further reading: